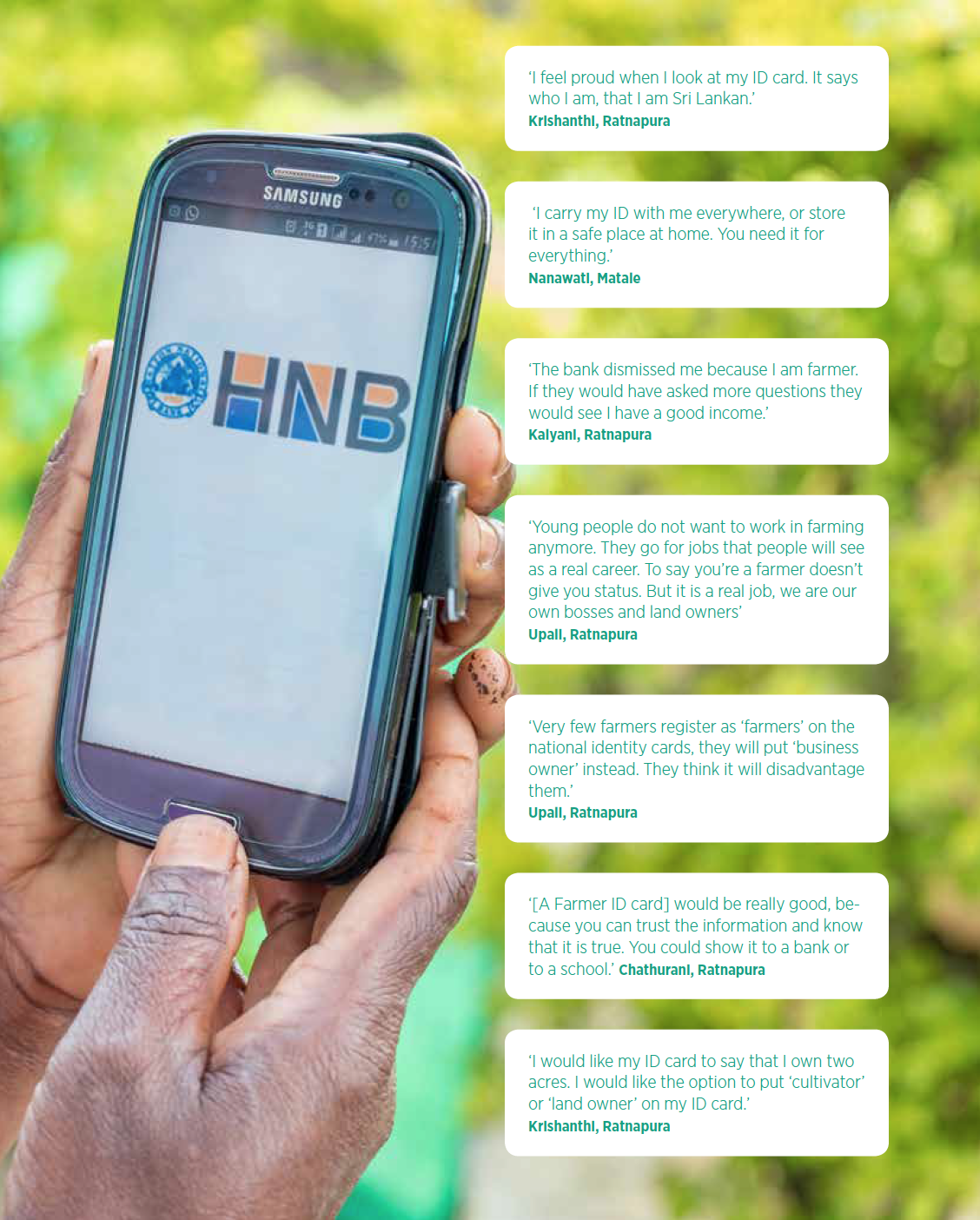

Smallholder farmers in Sri Lanka interviewed as part of the digital identity research

Recently, our friends at GSMA’s Digital Identity Programme and Copasetic Research set off to research digital identities and how they could support smallholder farmers in Sri Lanka. Their key hypothesis was:

“If MNOs, financial institutions, government and other service providers had access to a smallholder farmer’s ‘economic identity’ (income, transactional histories, credit worthiness, rights to/ownership of land, geolocation, farm size, and other vital credentials), they could provide access to more and better tailored services that enhance their productivity.”

In speaking with 40 smallholder farmers in Sri Lanka, as well as 7 stakeholders and 5 agri experts, GSMA learned a lot about the need for digital identities. GSMA invited LenddoEFL’s input in advance of the field research so we were keen to review the learnings. Below are some of the key findings of the report and how it relates to our work at LenddoEFL. If this is interesting, we recommend reviewing the full report.

Source: Digital Identity for Smallholder Farmers: Insights from Sri Lanka

Identity is valued, but farmers are unclear how it relates to additional benefits

In Sri Lanka, the government is rolling out a new smart ID card giving increasing access to official identity. But farmers do not immediately understand how new forms of identity can be used to help them get access to more services (e.g. more tailored information services). Once they make the connection, they see the value clearly.

Identity is valued as it relates to accessing credit

Farmers and banks do not connect directly in many cases and farmers tend to have informal manners of connecting to credit through their buyers and agribusinesses. Banks don’t always have the information they need to cater to farmers. And the microcredit model can be more of a burden on the farmers than it’s worth. The research found that smallholder farmers are happy for their trusted service providers to work together and share information to enable access to credit. But since many farmers receive their income informally, the thought of sharing this information too widely (particularly with the government) caused some concerns.

Source: Digital Identity for Smallholder Farmers: Insights from Sri Lanka

Digital ID must build on face to face relationships

In Sri Lanka, farmers rely on and trust institutions with whom they have built local, personal, face to face relationships and these will be the best channels to roll out new systems and technology.

Farming is changing

Climate change and globalization mean that the work of a farmer is changing. Traditional farming skills are no longer enough. Farmers need to be constantly re-considering which crops they will grow now and in the future due to changing weather conditions and fluctuations in profitability. Younger farmers in particular are looking outside of their communities to the internet for new information. This new information needs to be combined with better access to financial services, allowing farmers to finance the transition to new crops, and hedge some of the risks in experimenting with new approaches.

ID needs vary across farmer types

The research found that a farmer’s financial stability and the extent to which they are embracing change (i.e. changes to farming practices, or the use of new technologies) have the most significant influence on their digital identity needs and priorities. GSMA mapped farmers across a 2 by 2 with the axes of poorer → wealthier and embracing change → stuck/fearful of change. In each quadrant is a unique farmer with unique needs. See report for more.

All of this means there is opportunity to better serve farmers (and other small business owners).

Farmers need better access to formal financial services:

Digital financial profiles could allow farmers to access savings, credit or insurance more conveniently and cheaply. Note that farmers were concerned about sharing their income information with a lender for fear it would get to the government and increase taxation or reduce welfare support. Credit scoring using psychometric data could be a good fit for farmers as it relies on personality profile data created at the time of assessment rather than existing financial data.